![]()

Cranmer has an interesting blog entry on a call for dialog and peace between Muslims and Christians, unfortunately titled "A Common Word Between Us and You." His "Eminence" writes:

The letter sent by 138 Muslim Clerics to the Christian leaders of the world is both welcome and revealing. It is perhaps an inevitable consequence of the pluralistic nature of modern society that common ground should be found in order that followers of both Jesus and Mohammed can coexist, connect and communicate. Yet that geographical or sociological closeness gives rise to a theological and political antagonism, often blamed on war, economic inequality, and religious extremism.What is most impressive though is the analysis of the letter by the Anglican Bishop of Rochester, Dr Michael Nazir-Ali. While the whole of his analysis is worth reading, what is especially important for both Muslim/Christian dialog, but all interfaith and ecumenical conversations and projects is this point by Dr Nazir-Ali makes to the Muslim authors of the letter:

The letter is welcome because it is a joint communication from both Sunni and Shi'a scholars, and it is revealing because it is in essence a demand for submission. This is perhaps unsurprising, since the salvation of Allah is attained only through works, and the peace of Islam only through submission. By calling for unity, and setting out the parameters of 'A Common Word Between Us and You', the focus is on the lowest denominators – the love of God and love of one's neighbour. The problem is the absence of a doctrine of God, an understanding of the Trinity, and an acceptance of who constitutes one's neighbour.

The latter point is not semantic. Jesus was clear that everyone is one's neighbour, yet while Mohammed on occasion urged respect for 'the people of the Book' (ie monotheists), there is nothing but death and destruction consistently ordained for 'idolaters'. Thus this document offers nothing to the world's Hindus, Sikhs or Buddhists, whose practices presumably have to continue to be eradicated.

It is one thing to set out a grand theoretical statement, but quite another to articulate the praxis. The appeal is for all religions to work together, but Islam has set out its non-negotiable 'red lines' first. There is a veiled rebuke to Jihadists: 'And to those who nevertheless relish conflict and destruction for their own sake or reckon that ultimately they stand to gain through them, we say that our very eternal souls are all also at stake if we fail to sincerely make every effort to make peace and come together in harmony.' But the inclusion of 'for their own sake' is easily refuted by those for whom murder is in defence of Allah, and blessed martyrdom is the reward for their selfless sacrifice. The Muslim scholars further state: 'As Muslims, we say to Christians that we are not against them and that Islam is not against them - so long as they do not wage war against Muslims on account of their religion, oppress them and drive them out of their homes.' Again, the hand of friendship is extended on their terms; no mention of what may be the cause of the conflict or oppression. This basically says that peace and friendship are offered only if you cease your defence of and support for Israel; if you permit Shari'a practices in your countries; if Islam and the Qur'an are 'respected' and placed alongside your Christianity and your Bible.

'Please find out from us what we really believe. That is one of the purposes of dialogue. Ok, we may disagree about the nature of God but there are many other important areas of dialogue as well. There is justice, compassion, fundamental freedom, freedom to express beliefs, persecution of peoples. All these are matters of dialogue. Only one of them, the need for peace, is mentioned here.'

Dialog that is based first on discovering what our partners believe who seem self-evident. Sadly it isn't. Too often in not only interfaith and ecumenical work, but is pastoral work and in families, "dialog" is really parallel monologue in which we use each other as an excuse or medium for self-expression.

While self-expression is certain important and necessary (how many Christians, having little faith in Christ and no confidence in the gifts He has given them, simply out of fear refuse to speak what is in their hearts?), it can't come at the expense of love. All of the great and enduring values of contemporary liberal culture, freedom of conscience and religion, the right to free speech, of assembly and association, the valuing of private property and personal industry and responsibility, are all only possible if we move beyond parallel monologue and come to understand one another.

Yes, in the Church, Christ calls us to transcend not only our desire for parallel monologue and even the basic mutual understanding essential for a well-ordered and just civil society. But as I've pointed out before, without self-expression and mutual understanding the communion we are offered never moves from formal to actual.

Self-expression and mutual understanding are not the source of communion. Rather these good things, like all good things, are the fruit of communion: It is God the Holy Trinity, that Divine Community of Three Person in communion with each Other that is the source of creation. And it is only to the degree that I have accepted the invitation to participate in that Primordial, and Archetypal Divine Communion, that I am actually able to be self-expressive and enter into mutual understanding with others.

As we grow in our participation in the Divine Community we come to understand ever more fully that our self-expression, our dialog, and moments of mutual understandings are themselves sacraments of the Holy Trinity in Whose image and likeness we are created and to Whom , in season and out and in spite of whatever resistance we encounter, we must give all glory, honor and worship, forever and ever.

Please, if you have the time to do so, I would encourage you to read more from Cranmer's blog by clicking here: Muslim Clerics Demand Peace or Else.

In Christ,

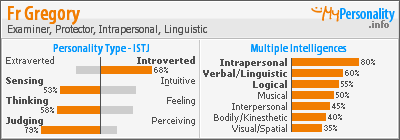

+Fr Gregory